This Too Will Piss You Off

And then one day, I was in the park. I was listening to a woman play her guitar. I wasn’t even really listening. She was playing so beautifully. The music seemed somehow to bypass my ears, find its way straight into my body.

As the music entered me, I stared at some ducks bobbing on the water in the pond. I became aware of the sun warming my skin.

And then this woman began to sing.

It didn’t seem terrible. It just seemed inevitable.

*

“I don’t know.” He sounded like he was going to cry. “But I have a theory.” He was holding in his pee. It was going to get out eventually, he knew. There was no way around it. There was nothing he could do about it.

“Can you not just listen?”

“I can. I’ve actually gotten quite good at that.”

He emphasized the word ‘that’, as though it was the one word he could count on to convey his meaning. It was like all the power of his thoughts funnelling down, arriving at the end of the sentence, the way his pee was funnelling down through his penis, arriving at the head, wanting to get out the little hole at the end. It was like his mouth was the little hole at the end of his penis and all the power of his thoughts was just a lot of piss bottled up, pushing that single word, ‘that’, into becoming italicized at the end of the sentence. As if ‘that’ were a tree standing alone in a field, erect and noble, not quite far enough from the forest to be truly, quietly alone, but not close enough to share the protection of the other trees. ‘That’ was sitting alone in his brain, getting blown over by the windy power of his thoughts, same as the power of the piss in his bladder was pushing to get out the end of his penis.

He told her his theory.

“I love you so much sometimes,” she said.

He stayed silent.

“But I also don’t like you very much sometimes.” She wanted a cigarette. She wanted to suck in smoke. “So, what’s your theory?” she asked. She sucked in a little air because that was all she had. She had no cigarettes.

*

They came in waves.

The first wave came in ships that floated on the sky. They dropped from the ships like spiders sliding down their webs until their feet settled onto the ground.

The next wave just appeared out of the air, like sudden apparitions.

The third wave burrowed up out of the earth.

The fourth wave swam up out of the sea.

Together, they pummelled the earth, until there was nothing left but a rind, like the crust from a piece of toast left on the plate after the sweet buttery centre is gone.

*

The first time she tried to answer questions on one of his thought sheets, she got it wrong–at least, according to him she got it wrong.

“A thought sheet is supposed to spawn new questions,” he said, “not generate answers.”

This pissed her off, mostly because it was so obviously exactly something he would say. She should have seen it coming.

She made a little sound, like a tiny cry for help, then went out and sat in the car, steaming up the windows with her breath. After a time, she started up the car and backed it out of the driveway. She went several miles, cursing him while listening to the radio. In the end, she drove home and demanded he give her another thought sheet.

“You can’t fill these things out properly when you’re pissed off,” he said.

This pissed her off even more. She was standing motionless in the front hall, still wearing her coat. He was at the top of the stairs looking down at her. She hadn’t even closed the front door. She heaved her purse up off the floor, flung it over her shoulder, and went back out, slamming the door behind her.

This time she kept driving till she was so far from home she didn’t think she could get back before dark. She was out in the middle of nowhere. There were no motels or anything, where she might stay overnight. She wanted very badly to stay out overnight, to make him worry. She could sleep in the car, she supposed. But that scared her even more than driving in the dark, so she drove home, and it actually wasn’t all that dark when she got home. She hadn’t driven as far as she’d thought.

The house seemed to be empty when she let herself in. She stood in the front hall, in the dark, for a long time, before turning on a light. She didn’t know where he was. For a moment, she didn’t even know where she was. Lost in some emotion she couldn’t quite name.

When she didn’t hear any sounds from anywhere in the house, she went up to the kitchen and put on the kettle. She was just sitting down at the kitchen table with her cup of tea when he came in and sat down across from her. She stared hard at him, really tried to see him.

He looked like he’d just woken up. His hair was sticking out sideways on one side, and his face looked crumpled. He didn’t speak, just stared down at the table while she sipped her tea. She wanted to ask for another thought sheet, but she couldn’t be sure that he wouldn’t turn her down again. There might be some rule about not filling out thought sheets this late in the day.

Fuck you, she told him in her mind, understanding suddenly what she was feeling. It was anger, but an anger so intense that it felt unfamiliar.

He didn’t seem to notice.

When he finally got up, he simply came around the table, kissed her on the top of her head, and told her he was going up to bed. As he walked away from her, he called back without turning: “Enjoy your tea.”

She felt a bolt of anger shoot through her. Enjoy this! she thought savagely. She tried to imagine something he wouldn’t enjoy at all, something she could ram up his ass. She was too angry to drink her tea. Too angry to think. Too angry to move, because it felt like it would hurt to move, like walking through fire.

What aggravated her most, she decided when she had calmed down a little, was that the boy would have been right, she never would have been able to fill out a thought sheet in her current state.

She got up and poured her tea into the sink, watching it swirl down the drain, then she rinsed the cup and stuck it in the dishwasher. She went into the living room. She was tired, but she didn’t want to go up and get into bed with him. She didn’t even want to be in the same room as him. She curled up on her side on the couch and pushed her face into a cushion.

The cat came out of nowhere and jumped up onto the couch. It sat by her bum. She reached down and put her hand on it, but she didn’t pet it, or scratch it under the chin. For some reason it felt to her like being nice to the cat would constitute some sort of concession that she just couldn’t make.

*

The pillows here are older, with the head, built up over time, made of stone. The mouth is puckered, a rich reddish rind on the eastern shore near the crack where the cheek is rent. Wind transports sand. The upper surface of the lake, its curve and orientation, take on form in a desperate moment of desire.

*

La La felt she understood something fundamental about Benita, and thus, indirectly, about herself. But the truth of the matter was, she knew dick. The misunderstanding arose in the fact that Benita didn’t understand what La La was talking about and was just practicing this expansive smile she had been working on for weeks now in front of the bathroom mirror. The ketchup and French fries were an unanticipated consequence. As for La La, she found Benita confusing, mainly because she was trying to pin down this unnameable thing about Lewis, a thing that gained its charm from being unnameable. So, for both girls, the real problem was unnameability. For La La, because she was desperately swinging her arms and flinging her head about in an effort to name this squirmy, slippery, unnameable thing. For Benita, because at the moment, she didn’t give a fuck about anything but her French fries, her ketchup, and her latest unnameable coiffure. Lewis had these perfect good looks, the perfection of which was heightened by the many small flaws in his appearance. It was these flaws that, each separately, and then again a while later simultaneously, exuded an air of perfection, which Lewis himself was completely unaware of, because in his experience nothing in his entire universe exuded anything at all. For instance, Lewis couldn’t get his hair to part where he wanted it to (he couldn’t get it to part at all) but he saw his obsessive desire to get it to part as a reflection of the fact that his hair was a certain kind of hair (passed on from his mother’s side) that was reluctant to part. For hours throughout the day, Lewis would stand before mirrors, trying to get his hair to part and, when it wouldn’t, he wound up hitting himself in the head with his hairbrush and screaming, “Fuck you hair!”

*

What we are experiencing now is extreme cold. This winter, I excuse myself. Every word I utter moves past summer. Last March, I purchased ashes. I was on another page of my next book, looking for announcements, trying to further my understanding of weather, searching for stories that might be coming toward me like storms, something to inspire me. Maybe we’ll be staying here longer than we thought. I wish to get crystal-like snowflakes caught in my lashes, laughing in the street, facing the challenges, discovering the things–difficult things with no regrets–educating my ears to what people are saying about the position of my children’s footwear on the shoe mat.

I am so completely rebuilding my professional life.

*

Debbie says, “Why does that sign say, Have your rad checked worms? Do worms have rads? Are they offering to check them?”

One of the guys in the backseat, obviously enamoured of Debbie, is trying to explain that there are actually two messages on the sign. One telling people to have their rads checked, the other pointing out that the same establishment that will check your rad also sells worms.

“You see?” the guy is saying. “On one line it says: Get your rad checked, and on the next line it says: Worms. They mean they have worms for sale.”

“It’s still a stupid sign,” Debbie says.

“Don’t you see?” the guy starts to say, but Debbie turns and gives him a look that completely shuts him up.

“Yes,” she says calmly, staring straight into his eyes, “I do see. I see exactly. And I’m telling you, it’s a stupid sign.”

“Not if you understand what they are trying to say.”

You’d think it was the guy’s own personal sign.

“It’s still a stupid sign,” Debbie says. “I don’t care what their intentions are. They made a dumb sign.”

The guy doesn’t say anything more to her. But then, a minute later, when Debbie turns away from him to look out the passenger side window, he starts explaining it again, this time to the guy in the backseat sitting on the other side of him.

The guy beside him nods now and then.

As the one guy goes on and on explaining, and the other guy continues to nod, Debbie looks up at me in the rearview mirror and rolls her eyes.

I roll my eyes back. Christ, I’m thinking as I take my eyes off the road long enough to have a good look at her, that Debbie. Even just her eyes in the rearview mirror make me crazy.

*

The improvement in communication around here is astonishing. First, we are all issued walkie-talkies. You can hear the goddam things clicking all the time all over the building. In addition to the walkie-talkies, they install microphones for the P.A. system at all the information desks, as well as at the switchboard. This means that everybody can stay in constant contact with everybody else at all times. The walkie-talkies are very heavy, but you look like a gunslinger with the thing hooked to your belt. I find I even walk different. Like I just got off a horse.

*

I put my arms around the old lady. What I was thinking was, don’t squish too hard because you might kill her, so I just sort of draped my arms around her and gave her a little kiss on the cheek.

*

I always pictured Fidel Castro as this firm but friendly Latin American guy who maybe smelled a bit of B.O.–maybe he didn’t wash quite enough–and who hung out in blown-up buildings and other dark, cluttered places, smoking cigars, drinking whiskey, and playing cards with a bunch of generals who laughed at all of Fidel’s jokes, even though most of Fidel’s jokes stank as bad as Fidel himself. All I could think as I sat there beside Fidel Castro was that the Blue Jays had beaten the Yankees in baseball last night. I was about to say this out loud, but just then Fidel Castro said, “Tell me about your wife. Do you have children?”

“Yes,” I said. “Yes, I do have children.”

Then it occurred to me to wonder why Fidel Castro would want to know if I had children. Maybe he wanted to kidnap them or something. But why would Fidel Castro want to kidnap my kids? What would he stand to gain?

“Tell me about your children,” he said in his charming Latin American accent. “They’re kids,” I said. “Average, everyday kids.” I stuffed a pretzel into my mouth and watched him carefully.

“I have kids,” he said.

This came as a surprise to me. I never thought a guy like Fidel Castro would have kids. I didn’t think he’d be married. Then I realized he probably wasn’t married. “How many kids do you have?” I asked. I imagined hundreds of kids, spread out all across Cuba, none with the same mother.

“Four,” said Fidel. “All sons.”

“Four sons, eh?” I said. “Wow. Where do they live?”

“At home. In Cuba. I live in Cuba.”

“I know that.”

I must have sounded insulted, because he apologized. “You seem very innocent,” he said.

I raised my eyebrows and nodded. What could I say? In a way, I suppose he was right. I was out of my league here, hanging out at a bar with a guy like Fidel Castro.

*

We sat for a while listening to the sounds of the parking garage, muted through the closed windows of the car. “You have to understand,” the professor was saying. He held a cigarette aloft, just below his chin. He tapped at the cigarette with his index finger. Ash showered off the end of the cigarette and drifted to the floor of the car. “Oh,” said the professor, looking around, “looks like we’re here.” He leaned over and popped open the glove box. God was in there with a woman. “Oops,” said the professor, “sorry.” He flipped up the door of the glove box, and it shut with a click. He turned to grin at me. “We should probably give them some privacy,” he said. We got out of the car and went into the mall.

*

The boy could see things exploding to the south, down in the city. And he could hear the loud, but somehow at the same time muffled sound of everything blowing up. He went to the coffee maker and put in a cup of water. He got out the grinder and filled the hopper with carmel flavoured coffee beans. He had a lot of carmel flavoured coffee beans.

*

I just want to know what happens, someone says.

It’s just emptiness, someone else says. It’s all just emptiness.

*

The raisin toast was a little too far beyond golden brown for the boy’s liking, so he slathered it in butter.

Upstairs, the girl wouldn’t wake up.

He reset her alarm and left her to her own devices.

Back again in the kitchen, the cat kept yowling.

*

The young wife was showing her husband some photos. They were photos of the husband standing in various places in a house he didn’t recognize.

“I think they’re from a time in the distant future,” the wife said.

The husband was wearing a silver jumpsuit in a number of the photos, and his face was very old, much older than now.

“Where did you get these?” he asked, touching his hair in places where it had gone grey in the photos.

The wife looked at him sideways, like she was trying to figure him out. “I was going to ask you the same thing,” she said. “I found them in your desk.” She turned one of the photos over. There was a date on the back.

“That’s sixty years in the future,” said the husband. “Where the hell did you get these?” he asked again.

The wife just shook her head. She held out one of the photos, this one face up, for the husband to look at. In it, the husband was naked. His body was saggy and shrivelled looking. “Gross,” said the husband, pulling his head back and grimacing.

“I know,” said the wife, laughing nervously. “You shouldn’t leave these sorts of things lying around,” she added.

The husband had never seen the photos, but he didn’t know how to explain this to his wife without sounding defensive. The wife hated it when he got defensive. He himself hated it. In fact, maybe it was only him who hated it. Maybe he was just projecting his own hate onto the wife. “You’re right,” he told the wife now. “What should we do with them? Should we burn them?” “No,” said the wife. “One day you might want them for a memory.”

The husband nodded. He already wanted them for a memory, which was weird, since they weren’t actually even a memory yet. What the hell are they? he wondered. “You should put them someplace safe,” said the wife, “someplace where no one can find them. Do you still have that book safe Derek gave you?”

The husband nodded. “I’ll put them in the book safe,” he said, smiling wanly at the wife. “And I won’t get them out again until they are a distant memory.”

The wife pursed her lips. “Well, maybe not too distant of a memory,” she said. “It looks like you’re on the cusp of death in these photos.”

The husband nodded again. It was true. It kind of scared him. But on the plus side, it looked as though he was going to live another sixty years – if that even was a plus side. Most of the people he knew who were over eighty were train wrecks, their minds gone. And they could barely walk. He’d sort of hoped that he wouldn’t last that long, that he’d maybe be dead before he decayed that much. But these photos made it hard to imagine that he was going to get his wish here.

“Put a reminder in your phone,” said the wife. “We can get them out again in thirty years and try to decide what to do with them then.”

The husband had been rethinking the whole thing while they sat there chatting about it. “Maybe if I burn them, it won’t come true,” he said now.

The wife sat quietly for a moment. Then she said, “I doubt that.” She knew about the husband’s desire to be dead before he fell apart. “You may be fucked in terms of your hopes about your life expectancy,” she said.

Once again, the husband nodded.

And then once again, they were both silent.

Finally, the husband got up, lifted his arm so that his wrist watch was close to his mouth, and told it to set a reminder for thirty years hence. Then he went down to the basement to try to find the book safe his friend Derek had given him all those years ago when they were young and foolishly believed in things that it was becoming rapidly more and more apparent were really truly foolish to have believed in.

*

I loved them in my own way. I did not complain about the cold wind. I spared no effort to steady the rifle. I never lost my cool. I became flesh. I swam. I sang in the air. I grew vain. I wiped my mouth. I wore shin pads. I knew this was the right place. I sold the whole lot the first day. I retreated to nearby. I stood like Matisse. I don’t often write. I wrote down the inscription. I hadn’t insisted. I wrote these lines: I am the farmer’s wife. I feel my red heart. I also missed Peter Tsaramiadis in Athens. I was signed on. I did not really believe it. I hadn’t expected the softness. I squatted by the fire. I lay for days in the sea. I am watched daily. I am not consulted. I have worried. I have less to lose now. I remember thinking: I am the centre. I can hear them moving. I am no traveller. I’ll see you in the morning. I will come again.

Ken Sparling

Ken Sparling is the author of eight novels: Dad Says He Saw You at the Mall, commissioned by Gordon Lish; Hush Up and Listen Stinky Poo Butt, handmade using discarded library books and a sewing machine; a novel with no title; For Those Whom God Has Blessed with Fingers; Book, which was shortlisted for the Trillium Award; Intention | Implication | Wind; This Poem Is a House; and Not Anywhere, Just Not. He lives in Richmond Hill.

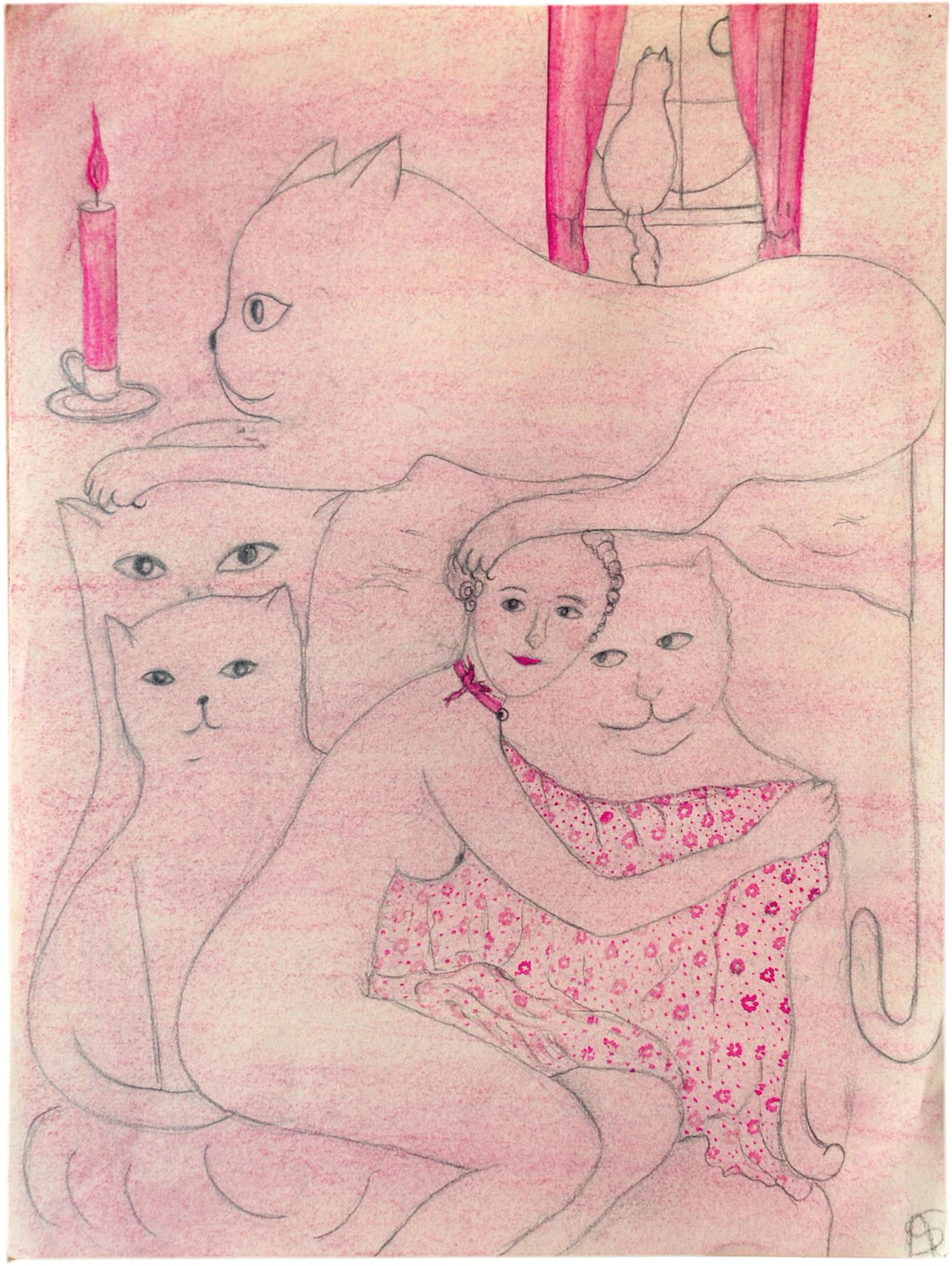

Aurélie Salavert

French artist Aurélie Salavert conveys her thoughts, feelings and memories into pictures that feel as if they were buried in our own subconscious. The thruline of her practice is drawing that continuously reinvents itself through her use of different techniques and styles, allowing a figurative abstraction to emerge. Salavert's vast output of intimate pencil drawings, with their gentle washes of watercolor or flat areas of gouache, speak to us in a childlike clarity, but their meaning remains open. As Stéphane Calais states in the text for the exhibition Une expédition at the Fondation Ricard, Paris, "She is looking for something, at times she finds something, and when she doesn't, we're happy being lost with her."

Aurélie Salavert graduated from the Ecole Supérieure des Beaux-Arts de Marseille in 1990. In 1992, she received a grant from the DRAC Provence-Alpes-Côte d'Azur - Ministry of Culture. Her work was featured in solo exhibitions at the Galerie Athanor in Marseille and The Calvet Museum in Avignon. A selection of her artworks was acquired for the permanent collections of the Fond Régional d'art Contemporain (Paris) and the Fond National d'art Contemporain (France), and individual works reside in numerous private collections throughout Europe and the United States.