Two Hats

First Stella Ziegler got struck by a car while crossing Sunset to catch her bus. Everyone saw from the windows. She hemorrhaged in the ambulance. Then Rishi Adhikari immolated, ignited by his electric razor. His family remains in reparative litigation with the manufacturer. Now Brendan. Done in by sleep on vacation in Hawaii.

I went to the kind of high school meant to inoculate its students against death. They kept armed guards at the gates. They paid off duty cops to explain to us how to avoid on duty cops. Nobody fought or failed out or got held up at knife point. They even decreased the homework load after Andrew Pratler snapped from the stress and beat his girlfriend with a hammer in the parking lot.

My mother told me about Brendan under the halogen lights of a supermarket. We’d been in the snacks aisle. I held a box of Nature Valley bars. She said, Brendan went to sleep last night and he hasn’t woken up. For a second, I thought that left a possibility he still might.

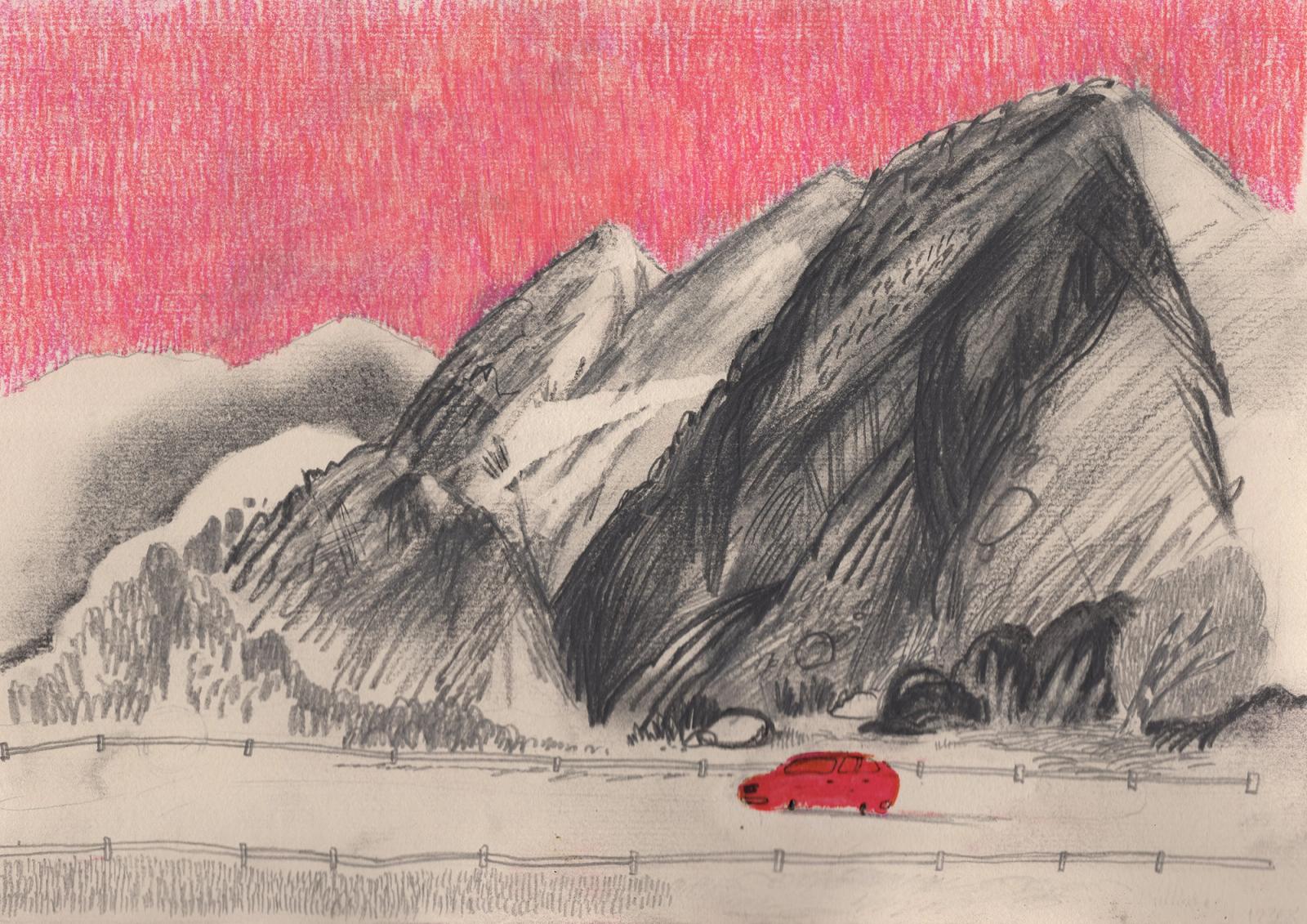

I was in Arizona to play in a tennis tournament called the Copper Bowl. I didn’t do very well. What I remember most is the mountains. How bare and red and immediate they looked against the blank expanse of open sky. I was sixteen, but I still didn’t know how to drive. Back then, I spent so much time being taken places. It’s different. Looking out the window when you’re not the one driving is so much more removed.

In Arizona, I saw decapitated mountains, strip malls, terracotta. I thought of the black, spongy rock in Hawaii. I thought about Brendan going to bed.

“It seems karmic,” Aaron said. “Or cosmic.”

We were on the football field during lunch period. I tended to believe Aaron. He’d been the first guy I knew to roll a joint successfully. He carried a pocket knife and kept a Nalgene bottle hanging on the carabiner affixed to his belt-loop.

I fingered the flecks of ground up rubber scattered through the turf.

“Karmic against what?” I said. “We’re good people.”

Gavin lay beside me on his back, clutching a frisbee to his chest, staring up at the sun. He wore an open flannel and cuffed pants and Chacos.

“Because we’re the rich elite,” Aaron said. “Despite our pretense to the contrary.”

“When you’re sixteen,” Gavin said. “You want to look poor.” He was a lanky, pale blonde of unspeakable beauty and immaculate stupidity. He didn’t have an original thought.

“I’m just saying,” Aaron said. “Nobody at Taft is spontaneously combusting.”

“Is that what happened?” Gavin sat up and tossed the frisbee on its end across the simulated grass, so that it landed and spun back toward us. “Another combustion?”

“He just went to sleep,” I said. “That’s all I know.”

“Steinman,” Aaron said. “Come on. You’ve gotta give us a little more here.”

I was the supposed expert. I knew Brendan from the tennis team.

“The family declined an autopsy.”

Wagner Von Schaff took me from school to the tennis club. He drove a Toyota Rav4. We stacked our bags on the back seat. Wagner put on the local country station. His mother curated an art museum. His father was a vascular surgeon at Cedars-Sinai. “All My Ex’s Live in Texas” played on the radio.

“I really relate to this song,” Wagner said. “Because all of my exes live in the Palisades.”

All of his exes lived in the same house, actually, because they were sisters. He’d dated all three of the Marines. Now they all hated him.

We followed Mulholland along its ridge toward the hilltop tennis club where we practiced. Through the window, I saw gated communities and the shattered gulf of the San Fernando. I lived at the top of the valley. I looked down upon it from my bedroom window. At the end of our street, dirt trails wound back into the Santa Monicas.

“I shouldn’t have done that,” Wagner said. “With the Marines.”

“Probably not.”

“She just had such incredible tits.”

“Which?”

“All of them,” he said, mournfully.

We played tennis well into the dark. I liked playing tennis. You couldn’t do it with any external layer of irony or self-consciousness. Wagner played tennis better than me, but that day I won. We didn’t talk about Brendan.

Brendan wore two hats. I don’t mean that metaphorically. He literally wore two hats. Baseball hats, one stacked within the other. Double bills and all. This became a trend after he died. Wearing two hats. Specifically, with the outer hat being a hat with the emblem of our school on it. The letters H and W, interlocked. Brendan was in line to be the valedictorian. He also wrote a music blog and he spoke Japanese and he got in Early Action to the University of Chicago.

I didn’t know Brendan very well. I found him to be pimply and oddly shaped and he played tennis contrary to my aesthetic preferences. Bad technique. Grunts.

Once, after a match, we shared a pizza together at the California Pizza Kitchen. He pronounced “chipotle” wrong. That was the kind of pizza we ordered—Chipotle Avocado Ranch. He inverted the t and p. He said “chitople” with such confidence and sincerity.

Brendan wasn’t very popular, but it was the popular people who now wore two hats. They started a Facebook group called the Two Hats Club. I wasn’t very popular. I wasn’t unpopular though. Brendan had been unpopular. Brendan had an older sister who, unlike him, was shaped normally. On Facebook, in The Two Hats Club, she posted a story about how he fell asleep once while skiing down a mountain.

My mother made chicken thighs with lemon marinade that she baked in a glass baking dish. She also baked broccoli in a steel baking dish and assembled a spinach salad with Newman’s Own dressing. We ate a version of this dinner each night. Sometimes the chicken was chipotle marinade or Italian dressing marinade or paprika marinade. Sometimes the broccoli was broccolini or cauliflower or asparagus. The salad was always spinach.

My father was the type of father who came home for dinner and sat at the table in his business casual work clothes and talked about how fortunate he was to be able to come home for dinner and sit at the table in his business casual work clothes.

My mother was the type of mother who had something wrong with her left eye. It had to do with the optic nerve. It just fluttered there, the eye. Unfocused. Not looking in the direction of the good eye. This gave the impression, when she looked at me, that there was something going on in the background I was blind to.

My father talked at us about how his boss wanted him to cancel one of the television shows he managed. It was a show with a ravenous fan base. The fanbase was getting too old, the show too expensive.

“It’s going to be a clusterfuck,” he said. “But news wants the timeslot. My hands are tied.”

My father mostly talked about himself, but he punctuated his talking about himself with questions about me.

He ended his discussion of the television show cancellation by asking, “How has the void of Brendan’s loss affected your meditations about college and your forehand and the projected doubles lineup.”

I said I didn’t want to talk about Brendan.

He asked if I had seen the grief counselor.

“I don’t want my kid talking to a shrink,” my mother said.

“Our kid,” my father said. “Don’t worry. Something like that will never happen to you.”

“He knows that. He knows he isn’t going to fall asleep and drop dead. That isn’t something that just happens. He’s sixteen. He isn’t a moron.”

“I didn’t call our son a moron.”

I ate another chicken thigh at the kitchen island. Then I went to my room and did homework while I listened to music, and the dog, Bailey, a retriever, lay on my bed and chewed on a Nylabone. She was a very good dog. Entirely untrained. Brutally stubborn. If I didn’t pet her to her satisfaction, she clawed me.

The Saturday morning of the memorial, before putting on my dress shirt, I walked Bailey up to the trails. We went all the way to the Missile Defense Station. People mistook the Missile Defense Station for a Missile Silo. It looked like a Missile Silo, in all its phallic glory, but, during the Cold War it actually held a computer. The computer was designed to alert The Government about any ballistics incoming over the Pacific.

The computer that was in the silo-like tower possessed, approximately, the processing power of the glitchy, screen-cracked phone in my pocket. Smog layered in the distance. On the rock face beside us was an old fresco, done as a part of a semi-guerilla art installation on and around the Defense Station. Little of it remained. The fresco of a house erupting with flowers had been graffitied first with illegible lettering and then with the green haired, red-lipped face of The Joker.

A group of mountain bikers hung around with their mountain bikes and squirted arcs of water into their mouths from their plastic, bike latching bottles. Dogs, both off-leash and on-leash, drank water from their owner’s hands, from their owner’s portable bowls, and from the chipped provided bowls that sloshed with milky, viscous spit.

Bailey investigated the ass of a pit-bull mix, then ingratiated herself with the pit-bull mix’s human father. She sat before his feet, extended her paw, and smashed the crown of her head into his crotch until he gave her a treat from his fanny pack.

I sat between Aaron and Wagner Von Schaff at the memorial. Gavin, who came late, stood at the back of the room. Wagner wore two hats. Aaron and I didn’t wear any hats. The non-denominational chapel was packed. People stood down all the aisles. My mother and father were there, somewhere.

The head of school recited profound, abstract remarks from trembling paper. Then a line-up of close friends, acquaintances, teachers, and coaches, recited remarks of varying profundity and levels of abstraction. Brendan’s best friend, Walter, read a post from Brendan’s blog. It was the final post, posted the night that he died. Walter had translated the post into Japanese and he read us the post in Japanese. I didn’t know what it said. I don’t speak Japanese. The blog got made private after he died. I couldn’t read it there, either.

His family then gave some very concrete, but not particularly profound, remarks. The story about skiing got repeated. This time the father told it.

“So, we were up on the mountain, and I look over and there’s Brendan, skiing down a mountain sound asleep.”

The sister told a story about when Brendan visited her at Brown and played beer pong for the first time. I don’t know what about him the story was meant to convey.

“He got very drunk.” She was laughing and crying at the same time.

As we all sat in the room remembering Brendan, a feeling of aliveness rippled through the crowd. Programs rumpled. Feet tapped. The shuffle of bodies murmured through the non-denominational chapel. The raw, throbbing life of us all must have been, for his actual loved ones, pretty weird.

Afterwards, we all poured out into the campus for a reception. A long line of catering trays was set up in the quad. Suited waiters walked with hors d'oeuvres. I loaded my plate with sushi, chicken breasts, pasta salad, French fries, and breadsticks.

I settled at a table with Aaron and Gavin. I saw Wagner walk by.

He stopped and grabbed me by my shoulders, “I’ve got to get out of here. All three Marines are in the building. I’m totally fucked.”

“We’re outdoors,” I said.

“Dammit Steinman. It’s an expression. It’s just an expression. Don’t you understand anything?” He pointed to a table, a tree, to me. “This is all a building.”

Aaron extended his plate of sushi to Gavin and I. I took a cucumber roll. Gavin declined.

“It’s funny.” Aaron chewed with his mouth open. “It’s always the ones who seem happy.”

Gavin fluttered his moronic blue eyes.

“My cousin,” Aaron said. “Chillest guy ever. He’s in a hospital now. For that type of stuff.”

He took his pocket knife, opened the blade, and stuck it into the octagonal wood table.

“I was hospitalized for approaching perfection,” Gavin said.

I gorged myself until the food was gone. Then I went back for more. I got creampuffs, spanakopita, chicken salad sandwiches, and assorted fruit. From a waiter, I took five crab rangoons.

I didn’t even make it back to the table. I stood alone by a lidded trash can and ate.

All my classmates in their polo shirts and dresses and two hats, holding paper plates, sipping from disposable cups. They stood in circles and sat in circles. My parents stood in a circle of parents next to another circle of parents. My mother was across from a man who talked with his hands. She tilted her head at him. I couldn’t see her bad eye. Behind the man was a cement wall lined with ivy. Behind the wall was a staircase and behind the staircase was a building with a single window open on the third floor. Behind the building was the sky.

I watched the mourning and talking and laughing and flirting until I couldn’t imagine saying anything to anyone. I couldn’t be trapped in a car with my family. I didn’t want to be driven home.

I left the quad and headed through the lot of shining cars, out onto Coldwater Canyon. The school was on a section of the road with no sidewalks. I waited on the shoulder as traffic whipped by in both directions. A red-tailed hawk eyed me from a barren tree. I looked left and went.

Jackson Frons

Jackson Frons has written for Joyland, Racquet Magazine, and Washington Square Review, among others. He lives in Upstate New York.

Varya Yakovleva

An artist, illustrator, director of animation from Russia, now in exile, based in France. Participant and an award-winner at International festivals of animated and feature films and illustration. Filmography: « Anna, cat and mouse » 2019, « Life’s a bitch » 2021, « Oneluv » 2022. Animation films have been selected for more than 200 festivals in total, and have more than 25 international awards. Varya Yakovleva has made 9 solo exhibitions in France, Norway, Finland, Cyprus and Russia and is a participant of more than 50 group exhibitions in different countries.